Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has dominated media in the United States — both news and social — and the reasons behind Putin’s attack and the implications it will have on our country and our allies are complicated, at best.

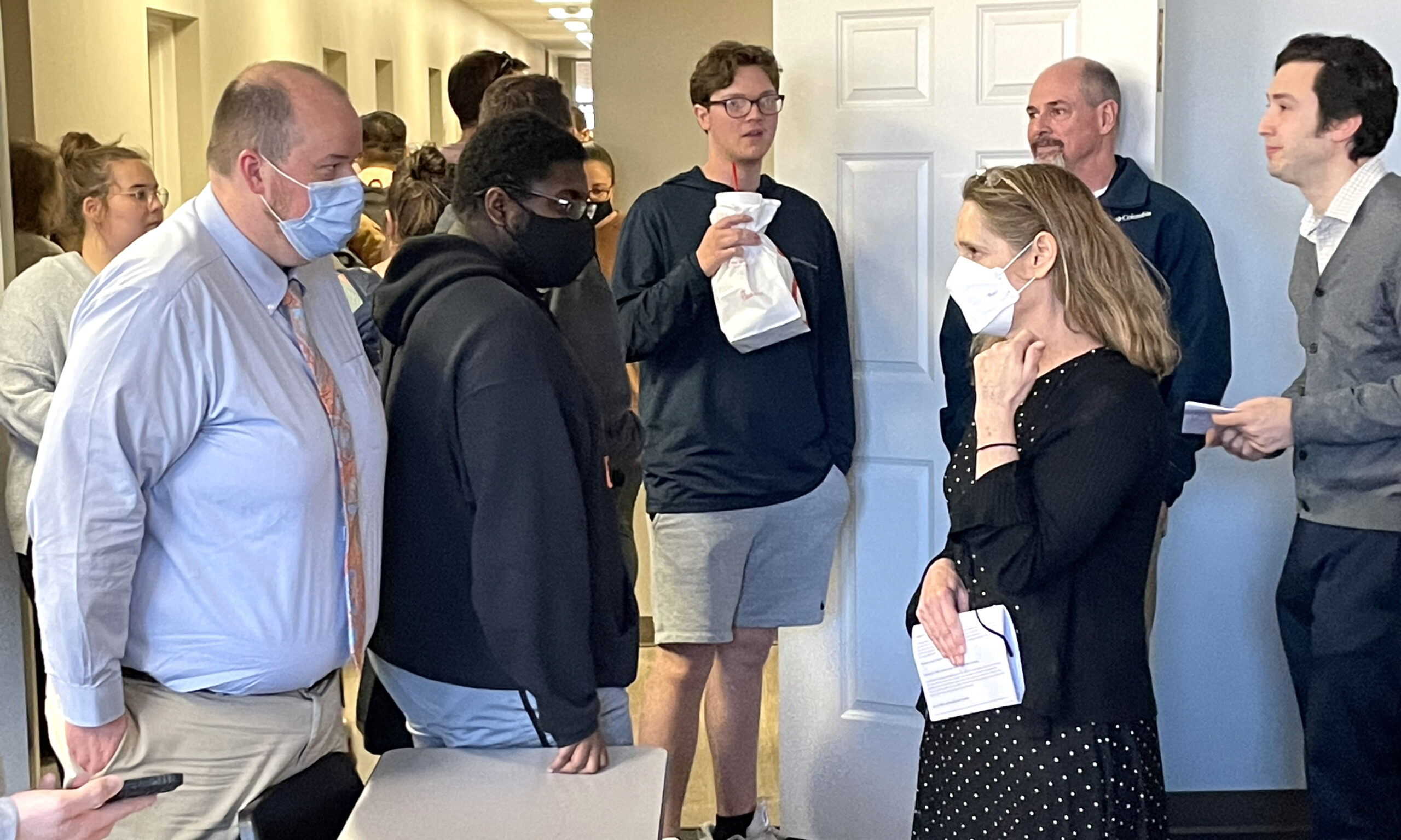

To help paint a clearer picture of the fighting taking place roughly 5,000 miles away, Campbell University history and political science professors whose research has included U.S.-Soviet relations, Russian studies and military strategy spoke to a crowded D. Rich classroom of Campbell students primed with questions.

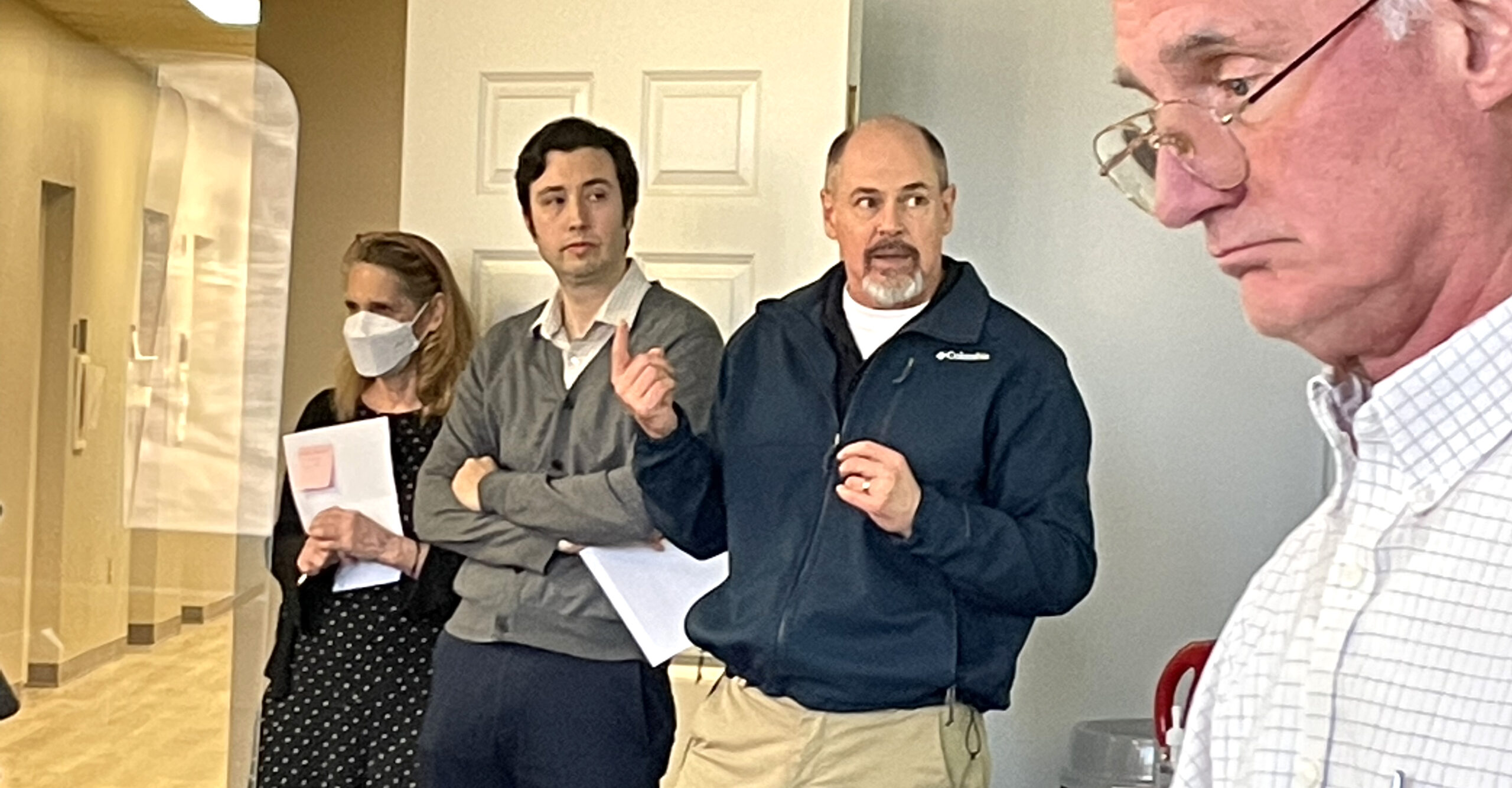

The faculty panel included Dr. Jaclyn Stanke, associate professor of history whose research has included U.S.-Soviet Cold War relations, and Cold War popular culture; Dr. Ethan Alexander-Davy, assistant professor of political science who earned his bachelor’s degree in Russian and ancient Greek from Amherst College and his Master in Philosophy degree in Russian studies from Cambridge (after spending a year as a Fulbright Fellow in St. Petersburg, Russia); Dr. David Thornton, associate professor political science and history whose fields of research has included international relations and European politics; and Dr. David Beans, assistant professor of security and computing NATO/European Union officer for the U.S. European Command in Germany.

“It’s unfortunate that most Americans learn their world geography when there’s a war, but I’m glad to see that this one has got your attention,” Thornton told a standing-room-only crowd of students on hand Tuesday. “It deserves it. This is a very serious and dangerous situation in Ukraine. You dig back in history and try to find comparable circumstances, and the only ones you run across really don’t work out well. But this [forum] isn’t about optimism or pessimism, but instead to realistically assess what is happening.”

For Stanke, the news in Ukraine has affected her both professionally and personally. She has spent years studying the Cold War and has taught both U.S. and Eastern European history at Campbell, and she has visited the country twice in the past 12 years (in 2010 and 2016) — before, she says, the recent rise in Ukrainian nationalism. She helped kick off Tuesday’s discussion by giving historical context to the events that led to Russia’s invasion. She began with 1991 and the dissolution of the Soviet Union, which led to 15 republics (including Ukraine) declaring their independence.

While relations with Ukraine and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) began in 1992, plans for the country’s joining the alliance were shelved in 2010 with the presidential election of Viktor Yanukovych, who preferred to keep Ukraine non-aligned. Yanukovych fled the country in 2014 during the Euromaidan unrest, when protests erupted over the government’s decision to cut European ties and align closer with Russia and the Eurasian Economic Union. Later that year, Ukraine’s new government made joining NATO a priority, and in 2019, the country amended its constitution to plan a strategic course for membership into the European Union and NATO.

“For a variety of reasons, Russia was starting to feel a little more threatened by the expansion of EU and NATO membership, and the reasons for that run deep,” Stanke told the audience. “But during this time, Ukraine’s population has been kind of split — if you would have looked at things in 2010, you would have found an evenly divided pro-Russian, pro-West split.”

Stanke said that as troop build-up at the Russia-Ukraine border grew, she still didn’t believe a full-scale invasion was imminent. But the rise of Ukrainian nationalism and their flirtation with NATO and other European alliances pushed Russian President Vladimir Putin over the edge. She believes the invasion has only strengthened that nationalism.

“Whether this is a short or long fight, it’s going to take a while for Putin to eradicate that,” she said. “But my fear is that he’s going to start using very brutal methods. I have friends and colleagues in Ukraine, so this has become very personal for me.

“And I love Russia. I know that sounds really weird to say now. But I would love to go back.”

Alexander-Davy began his presentation by comparing Russia’s invasion to the Peloponnesian War (Athens and Sparta in 431-401 B.C.) and the siege of Melos, a small island in the Aegean Sea roughly 70 miles from Greece. The Athenians demanded the Melians submit to them and pay tribute, but the Melians insisted on their independence. It didn’t end well for Melos — the men were all killed, and the women and children were sold to slavery.

“In some ways, we’re not quite as barbaric as we were then,” he said. “But perhaps in some ways, we still are.”

According to Alexander-Davy, Ukraine’s potential alliance with NATO has played a huge role in Putin’s decision to invade. He compared it to the U.S.’s assumed reaction if a neighbor like Mexico were to enter into a military alliance with China — smaller, weaker countries just don’t have the same freedom to choose their own destiny, he said. He also pointed to Putin’s nostalgia for the Russian Empire and the concept of Russkiy Mir, or “Russian World.” Putin justified the annexation of Crimea in 2014 with Russkiy Mir, calling Russia a “divided nation” and speaking of the need to “restore unity” to protect the country from the West.

“None of what I’m saying is meant to justify or provide any moral justification for Putin’s actions,” Alexander-Davy said. “What’s happening in Ukraine is truly horrific. But this is about understanding your opponent and working to avoid the kinds of outcomes we’re seeing here.”

He called into question the U.S. policy regarding Ukraine — essentially encouraging Ukrainians to “play tough” with the Russians at the risk of “getting wrecked.”

The question-and-answer portion of the faculty panel lasted about 30 minutes with students asking questions about China’s potential involvement, protests from Russian citizens and that nation’s falling economy and the possibility of a nuclear attack. Students were also concerned about the invasion’s impact on the United States, both economically and on the military.

Beans, who in addition to his work with NATO/EU and the U.S. Navy was a faculty member for the U.S. Air Force and National Defense University, said he believes the U.S. and its Western allies are being cautious while also strengthening their NATO alliance.

“I think if Putin were to launch a nuclear attack, he would be quickly removed,” he said. He also offered insight as to why the U.S. and the world cares so much about this particular invasion.

“Why is Ukraine significant? It’s the second largest country in Europe, behind Russia,” he said. “There are a lot of natural resources, and it’s part of the ethnic heart of Russia. Communist revolutions in the past were centered in Ukraine. There is this idea of identity. And Putin thought when he rolled in that it was going to fall quickly. And it hasn’t happened.”