Gaylord Perry, a two-time Cy Young Award-winning pitcher who won 314 games and struck out 3,534 batters over his 22-year professional career and an inaugural member of Campbell Athletics’ Hall of Fame, died this morning at his home in Gaffney, South Carolina.

He was 84 years old.

Perry attended then-Campbell College from 1958 to 1960 in between stints as a Minor League pitcher in the Texas League. He was called up to the majors at the age of 23 with the San Francisco Giants in 1962, where he pitched in 13 games and compiled a 3-1 record as a rookie. He would go on to become one of the most durable and unique characters in the sport, known for his “spitball” and a deep arsenal of pitches.

A native of Williamston, North Carolina, Gaylord Jackson Perry and his older brother Jim grew up on a tobacco farm and learned to pitch during breaks while working in the fields. Both were star pitchers in high school and both signed to play professional ball straight out of high school — Jim in 1956 with the Indians’ farm system and Gaylord in 1958 with the Giants.

The two would go on to become the first (and still only) brothers to win a Cy Young Award, and their 529 combined wins is second only behind Phil and Joe Niekro’s 539.

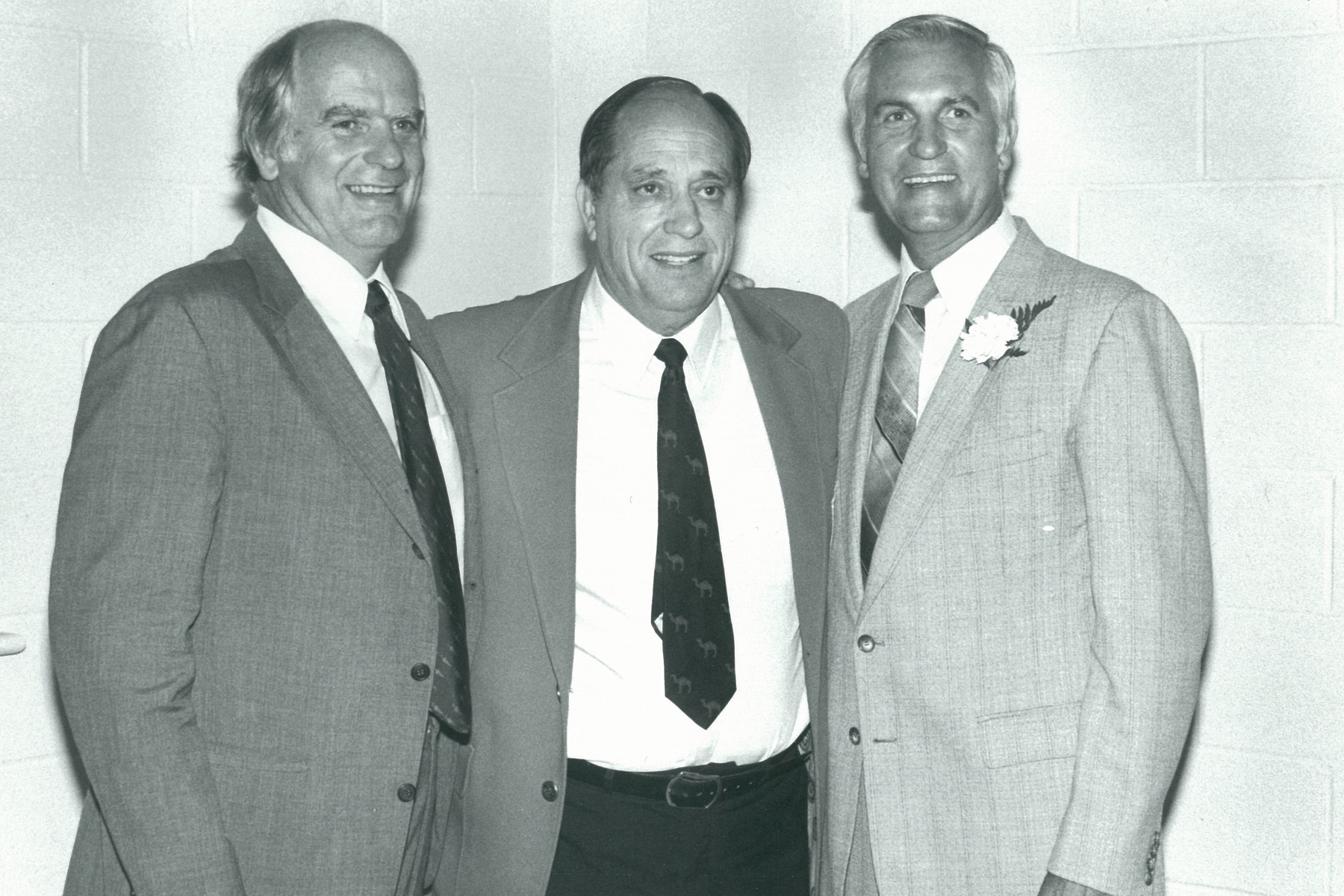

Jim Perry, who joined his brother as the first two Campbell Athletics Hall of Famers in 1984, released a statement on his brother’s passing Thursday:

“As I think about the passing of my brother, I am reminded of the many good times we shared. Growing up together on the farm, we made up a homemade ball and learned the game of baseball playing with our Dad during noontime breaks from picking tobacco. We were both proud to attend Campbell as we transitioned from high school to the professional ranks.

“As his big brother, I tried to set a good example for Gaylord and I was proud to see him follow in my footsteps and to watch him forge such a great career. In the major leagues, it seemed that we often pitched on the same day and one of the greatest days in both of our careers came the same day Neil Armstrong first walked on the moon. I won two games on the same day and Gaylord hit his first career home run!

“We were the first brothers to pitch against each other in the All-Star game, the first to both win 20 games in the same season, and the only brothers to both win the Cy Young Award. We took pride in our durability and perseverance in finishing what you started during a time when that was considered the mark of a great pitcher.

“My brother was a true character and ambassador of the game. He will be missed. My wife, Daphne, and I send our heartfelt condolences to Gaylord’s children as we share the grief of his many fans and supporters.”

— Jim Perry

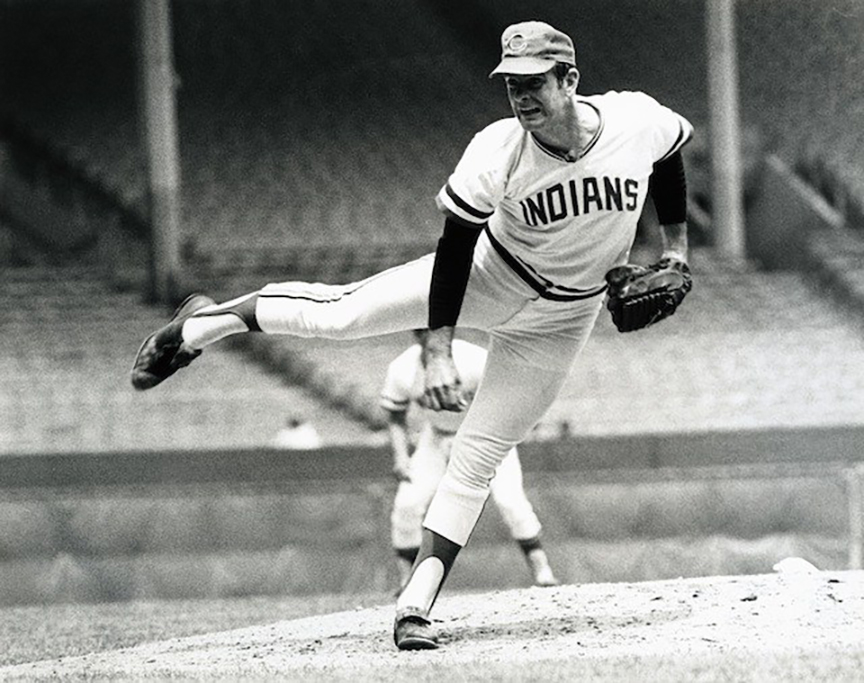

Gaylord Perry won the Cy Young Award in the American League in 1972 with the Cleveland Indians, and then again in the National League in 1978 with the San Diego Padres to become the first pitcher to win the award in both leagues. He would go on to pitch for the for the Giants, Indians, Texas Rangers (twice), Padres, the Yankees, the Atlanta Braves, the Seattle Mariners and the Kansas City Royals.

During his career, he won 314 games and lost 265. He struck out 3,534 batters in 5,351 innings and compiled a 3.10 earned run average.

Perry was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame at Cooperstown, New York in 1991.

From the New York Times:

Gaylord gained a measure of infamy as one of the most accomplished spitballers of his time with an arsenal of saliva and various lubricants.

The use of saliva and other foreign substances on the baseball, often collectively referred to as spitballs, as well as scuffing the ball — all designed to make pitches break unpredictably — were outlawed in 1920, though a few designated pitchers accustomed to defacing the ball at the time were allowed to continue doing so until they retired.

Since 1920, many pitchers have been accused by opposing teams of cheating by doctoring the ball.

Those pitchers almost invariably proclaimed their innocence, but Perry told of his outlaw behavior in 1974, while in his prime, in the book “Me and the Spitter: An Autobiographical Confession,” written with Bob Sudyk, a Cleveland sportswriter.

Perry wrote that his Giants teammate right-hander Bob Shaw taught him the spitter in 1964, when he was first starting to develop his legal pitches.

He said that after wetting the ball with saliva, he graduated over the years to “the mud ball, the emery ball, the K-Y ball, just to name a few.”

“During the next eight years or so, I reckon I tried everything on the old apple but salt and pepper and chocolate sauce toppin’,” he wrote in the vernacular of his rural North Carolina roots.

Sometimes he feigned drying his fingers on the resin bag on the pitcher’s mound but kept the saliva intact, and sometimes he put slippery substances at various spots on his skin.

To confound batters further, he often touched his uniform and cap before his windup to make them think he was loading the ball even when he was not.

Perry maintained in his book that his outlaw behavior had finally come to an end, saying: “I’m reformed now. I’m a pure, law-abiding citizen.”

From Campbell Magazine:

According to baseball lore, Gaylord Perry was taking batting practice when the aptly named San Francisco Chronicle sportswriter Harry Jupiter noticed the rookie pitcher’s hard swing and suggested to Giants manager Alvin Dark, “This Perry kid’s going to hit some home runs for you.” Dark turned to Jupiter — as Perry tells it in a July 13, 2009 issue of Sports Illustrated — and replied, “There’ll be a man on the moon before Gaylord Perry hits a home run.”

Dark’s prediction would hold true over the next seven years. While Gaylord would win more than 80 games and become an All Star in his first seven and a half years on the mound, his hitting was about what you’d expect from a pitcher. His batting average by the late 60s hovered in the low .100s, and a career of nearly 500 at-bats had no home runs and only 13 total RBI to show for it.

Gaylord brought an 11-7 record into his start against the Los Angeles Dodgers and starter Claude Osteen on July 20, 1969. More than 32,000 fans showed up for the 1 p.m. matinee.

Seven minutes after Gaylord’s first pitch, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed on the lunar surface.

Approximately 25 minutes later, Gaylord stepped to the plate against Osteen and drilled a shot to centerfield that, to his amazement, cleared the wall. It was his first, and one of only six he’d hit in his 22-year Hall of Fame career.

He also pitched a heck of a game that day, too — going all nine innings and striking out six Dodgers in the Giants’ 7-3 win. But it was his “Moon Shot” that the Perry family will always remember.

One sportswriter quipped in the following day’s paper: “The way Gaylord Perry swings a bat, he stands as much chance of hitting a home run as … oh … as a man does of walking on the moon. Well, Perry and astronauts Neil Armstrong and Edwin Aldrin made it together Sunday.”